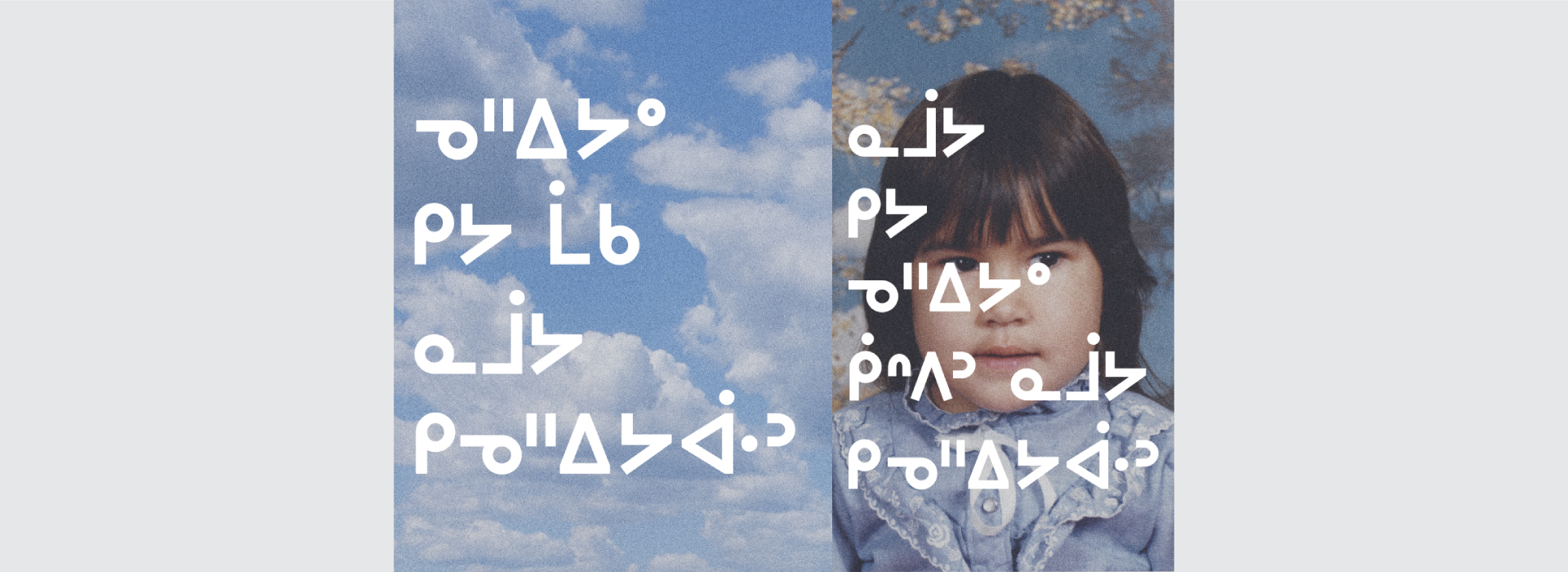

kiya itako (be you)

Joi T. Arcand

September 25 – ongoing

Lightbox (MOCA West Exterior)

kiya itako (be you) by Joi T. Arcand consists of two Nēhiyawēwin (Plains Cree) phrases written in syllabics set atop imagery of a prairie sky and a photo of the artist as a child. The work is presented across two venues: MOCA and Mercer Union. Arcand’s work at MOCA can be seen on the exterior west facade. The translation of the phrase at MOCA is:

“nēhiyaw kiya māka namōya kinēhiyawān”

“You’re not Cree If you can’t speak Cree”

The translation of the phrase at Mercer Union is:

“namōya kiya nēhiyaw kīspin namōya kinēhiyawān”

“You’re Cree but you can’t speak Cree”

MOCA’s first billboard installation with Arcand and an accompanying text by John Hampton have been commissioned in collaboration with Mercer Union, a non-profit, artist-centred space about a 10-minute walk from MOCA at 1286 Bloor St W.

kiya itako (be you)

kiya itako (be you) presents two mirrored Nēhiyawēwin (Plains Cree) phrases written in syllabics. One phrase, set atop a prairie sky, is installed outside of MOCA Toronto; the other, on a childhood photograph of Arcand, is installed outside Mercer Union. The two sentences come from words spoken by Joi T. Arcand’s mentors, offering contradictory descriptions of Arcand’s “authenticity” as a Cree woman and as a second-language learner of Nēhiyawēwin. The words speak of the importance of language to cultural identity and of the anxieties, hope, struggle and loss surrounding that relationship.

In 1892, Richard H. Pratt wrote, “Kill the Indian, and save the man.”¹ Shortly afterward, he founded the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, a model for nearly every other industrial/residential school across the United States and Canada. Pratt was an ardent proponent of cultural genocide as a more civilized alternative to the literal extermination of Indigenous peoples (which was the de facto aim of the US government at the time). He believed the elimination of Indigenous languages and cultural practices would be just as—if not more—effective a means for erasing Indigenous presence.

When an elder says, “Language is the key to our survival,” they are resisting this genocide. But this sentiment—as well as its less generous cousin, “You aren’t Indigenous if you don’t speak your language”—places the essence of Indigeneity in languages that very few individuals know. But how does one adequately learn a language without people to speak with or access to communities that offer language immersion? How can one think in a language when only broken phrases have been learned from an aunty, an app or during week-long retreats? And how can tools for communication—which vary widely across nations and territories and have undergone continual evolution throughout history—be the sole repositories for an entire culture?

These are the central tensions within which Arcand’s work exists, a widespread struggle to recover language and a sense of self in the shadow of cultural genocide. Arcand’s imagery investigates the aesthetic, cultural and communicative meaning of Nēhiyawēwin while demanding a confrontation with legibility—she asks, Who has access to the knowledge carried within language? Although Cree is the most widely used Indigenous language in Canada, those who speak it account for less than 0.3% of the national population, and even fewer still are able to read syllabics.² Here in Tkaranto, syllabics are more likely associated with Anishinaabemowin rather than Cree. This is because Nēhiyawēwin is not native to Tkaranto.

Monolingual Anglophones, who may interpret Arcand’s pieces as “foreign,” are partially correct if one follows a hyper-localized understanding of place. But these definitions of territory don’t take into account that Nēhiyawēwin was likely spoken on this land long before English, since Indigenous ancestors were multilingual and they travelled through territory exchanging knowledge. Languages travel too.

In the future, we may see something completely foreign to current languages. What comes from a Chikasha learning Cree on Dakota territory? Or an Anishinaabeg misreading Nēhiyawēwin syllabics and finding something new? Somewhere in the ambiguity of this intersection—moving from nostalgia to constructive illegibility—there is space for understanding that doesn’t annihilate the cultural meaning imbedded in its constituent parts but instead reaffirms their vitality. In between the foreignness and familiarity of these pieces, in between truth and falsehood, there is a new reality striving for articulation.

—John Hampton