Kirby Ian Andersen is a visual artist based in Toronto. Learn about his wide range of work in painting, sculpture, and installation work and more specifically about projects like IOTA, a decentralized painting project that travels in parts all around the world but remains connected conceptually as well as a crowd-sourced painting project that exists to involve the participation of artists from all corners of the globe.

coOp Art. Oilstick on canvas. Courtesy the artist.

What was your most memorable visit to MOCA?

It was an opening at the Queen location, and it was the crowd that sticks in my mind — eclectic and inclusive, artists, collectors, civilians, people from all backgrounds, ages, lifestyles. The art was great, the mood was big, and welcoming. That’s what MOCA has always done well.

Describe your current project, IOTA, and the ways in which you’ve adapted it to keep it active during the current COVID-19 crisis.

A little while ago I made IOTA, a decentralized painting — one large work in thirty smaller parts distributed to different locations around the world. Collectors or institutions agree to let their piece to be shown every 10 years with all the other pieces. (The work is to show now too, with voids as it disperses — so far there are pieces in L.A., London, Phoenix, etc). Each part functions as its own discrete artwork, but is connected to something way bigger — physically, conceptually, spiritually — and the work grows in context, gains aura, as its components travel across distances and through time creating more connections and narratives. I’d love the work to exhibit a thousand years from now (uh, if we’re out of quarantine by then), with a huge catalog relating the stories of all its owners and journeys.

IOTA. Courtesy the artist.

During Covid I’ve been thinking even more about how we are all connected (or isolated). I just started a crowd-sourced painting; people around the world can participate in the creation of the work (about 40 have already) by choosing, at my website, a small rectangular space within a grid on this big canvas. They select a color, and I fill in their chosen area with oilstick and add a smaller gestural stroke on someone else’s nearby rectangle, and so on until the canvas is full. (People can see the work in process online). I want it democratic, billionaires next to students, Moose Jaw beside Mumbai, but also I think people should commit a little, so each rectangle is ten bucks (but a group could buy one). What will the final work look like? Not sure, but, unlike Covid, it turns uncertainty or unpredictability into something hopeful, even beautiful.

Another solution has been to make smaller works on paper that can be easily mailed, since collectors can’t come in person. You know, I also make music and it’s fascinating to see how immaterial art like a song can have a much broader reach than a physical object. (I just saw via analytics that my track “Mrs Major Tom” was getting plays in Ishim. My paintings will never make it to western Siberia). So, I might do some high-res digital works for download and self-printing.

My deep interest though, is ambitiously-scaled physical works, which is always hard to do but especially these days, so I’ve been working digitally on some public sculpture and bigger ephemeral installation ideas. Will they ever be physically realized in this new world? Hope so. I can’t help but be optimistic about the future.

How did you first become interested in painting and sculpture?

I think I was doing cave paintings in the womb, or maybe even further back. Like in Lascaux 20,000 years ago. I do distinctly recall finger-painting in preschool and knowing deeply I was to do this for my life. By middle school I was holding conceptual art shows in my parents’ basement.

You speak a lot about themes of ephemerality, infinity, and looking into the future with your work. Why do those ideas attract you specifically? What significance might those ideas have during these very particular times?

I think we live many lives over time, crossing genders, races, cultures, abilities. In my art I often use small component parts to create a much larger object and gestalt idea. Kind of like how one ephemeral lifetime is part of an infinitely bigger soul experience. From that perspective, our time in quarantine is a blip. I’m interested in endless possibility, and the long view, like can I create a work that changes over hundreds of years, so that each generation will see something new?

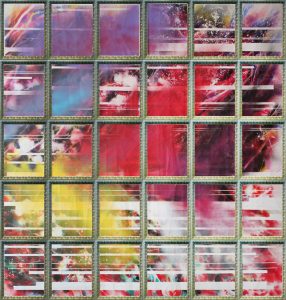

I started using component parts when I lived in Tokyo. I was making collages out of interleaved strips of imagery and some were so large I had to make them in sections in my tiny apartment. But those sections also enabled me to disrupt the initial image by rearranging them. So, the work could evolve even after its creation. I continued this idea after moving to L.A., doing works on bigger wooden panels, and then in Toronto using smaller aluminum panels but many more (more possible arrangements). For a show here I intermixed 5 separate paintings into a floor-to-ceiling 25’ long wall installation. A couple years ago at a Banff Centre residency I did a huge floor installation made from hundreds and hundreds of components parts. And that was just the beginning, more stages are to be made in other locations. It’s a permanently unfinished work. Even as is, it can infinitely change in shape and content. It’s monumental but ethereal, something I’m trying to do more in permanent sculpture — fixed in space but visually shifting. Material mirages.

Acceleration Still. Courtesy the artist.

You’ve lived in a lot of different places around the world, how has your ability to be mobile and migrate influenced the way you think of creating and collecting art?

For a long time I never had a studio. I worked everywhere, on rooftops, freight elevators, shorelines, on the ground on snowy fields. I still do sometimes, but now as a way to geotag or timestamp info into works — for example I squatted all day making paintings under a foot bridge in rain at McMichaels, like some kind of art troll, to make paintings that will be spliced with works I made in Banff, and some I’ll be making on the east coast, and maybe up north, all using found weather.

CRISPR SCULPTR. Courtesy the artist.

I also have made art from the stuff around me. So, in Asia it was Japanese manga, Nepalese movie posters, Turkish newspapers. Here in Ontario I’ve used found flora and stones and so on to make paintings. I’ve sliced and remixed ads, made massive snow collages on frozen lake beds, wheat-pasted silver paintings around cities. I’ve also held guerrilla exhibitions (with openings) in telephone booths, postcard racks in stores, subway stations. (I’ve had my eye on the MOCA stairwell ever since it opened).

A lot of my work, like IOTA, or even the sculptures or installations like CRISPR, is modular, so not only can those works be reconfigured to show in different settings, they can be packed and shipped and stored fairly easily because they can be broken down. IOTA could fit in a small briefcase. I must’ve had many past lives as a nomad, maybe that’s where it comes from.

What are some inspiring artists or art works you’ve come across that are responding the current crisis in creative ways?

My way of getting past the isolation at home is to go online and be in awe at massive projects by Zaha Hadid or Santiago Calatrava. Or even Space X. Or read sci-fi by Iain M. Banks which have kilometer long spaceships in them, and look at websites about crop circles, mathematical glyphs in wheat that last only days, or about Gobekli Tepe, which was built 12,000 years. I love things that make me wonder.

Where can we find more of your work in the digital space?

On my site there’s tons of stuff, and check out the blog portion because there’s a lot more about works like IOTA and CRISPR SCULPTURE, the spliced series, and current projects like the crowd-sourced painting and so on.

Questions? Reach out to membership@mocalegacy.webpreview.site

Banner Photo by Gabriel Li.